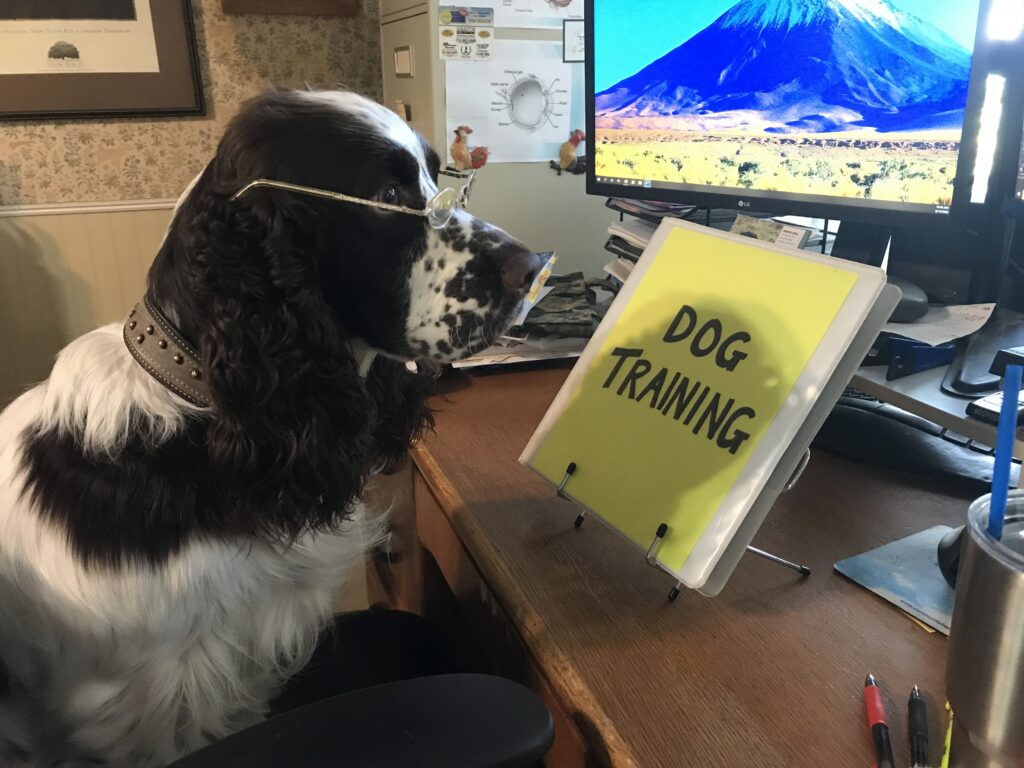

A recent student was practicing loose-leash-walking with her dog near a mat on the floor. When the team came within about 2 feet of the mat, the dog headed over to it to lie down. The leash was a cue to walk with her owner, but in the presence of the mat, the mat was a stronger cue. Some might call it a distraction, and it was, in this context. She was trying to focus on leash work, not mat training.

Cue Response Becomes Automatic

Actually, in becoming a predictable, reliable behavior, the process had become somewhat automatic. The dog didn’t stop to think about how to respond to the mat, it just happened. Developing a behavior so completely that the animal responds quickly and with perfect form, every time the cue is given, is a common training goal. All those early steps in training are all about getting to the point where the animal does the behavior immediately, in beautiful form, and every time. The process becomes automatic much like some of our driving skills become automatic and resistant to change.

It’s important for us to understand the impact of behaviors becoming automatic in training. If our dogs learn things we don’t want them to do and those behaviors become automatic, it’s much harder to re-train them. It relates to The Matching Law. Learned behaviors don’t ever go away; they show up in proportion to how often they were reinforced, for the life of the dog.

Which Cue is the Right One?

Though having the leash on was a cue for the dog to walk at her owner’s side, when the mat came into the picture it caused some conflict. We can immediately tell which of these behavior sets had been reinforced more. (Lying on a mat or walking with the owner) Cues are meant to give us the opportunity to ask our dogs for the behaviors we want. We have to be careful about the situations in which we give cues. There are so many more cues than the ones we are aware of, and many of them come from places in the environment other than our mouths!

Cognitive Resources

Cognitive psychologists teach us about attention, meaning choosing what stimulus to pay attention to in a given moment. When dogs are focusing on carrying out a behavior, perhaps sitting for some duration of time they haven’t before, it’s something new they are learning to do, somewhat difficult, and it requires a large amount of cognitive resources. That’s why, when we are increasing duration in a behavior like “sit”, we reinforce frequently. It’s hard for a dog to keep paying attention to the behavior they are essentially repeating over and over – sitting, continuing to sit, sitting longer – until the cue to get up finally comes. They are making a series of choices to continue to perform the behavior. Our goal is to reinforce every choice that is in line with what we’re asking them to do.

Another goal is for the dog to not make an error like getting up, because we know that those errors go into their repertoires just like correct behaviors do. So we try to give a reinforcer at just the right moment, after a period of time that offers just the right amount of challenge but allowing success; before the dog reaches the point where he makes the choice to get up.

Cognitive Overload

Dogs use cognitive resources to make this continual series of choices and that means their cognitive load is big. Just like humans, when the cognitive load is very heavy, dogs become more susceptible to distractions. This is why we don’t ask dogs to sit for half an hour as soon as they are successful at sitting for one minute. At that point in learning, the dog would be susceptible to the smallest distraction, getting up and walking away at the point where their cognitive load had become too heavy to handle. By building up duration slowly and carefully, we gently stretch their abilities to continue the behavior without using up too many cognitive resources. The behavior starts to become automatic, at which point the cognitive load is smaller, the behavior itself is valuable to the dog because of the reinforcement history, and distractions have much less impact.

You Use Cognitive Resources, Too!

Compare to yourself, when you’re learning something new. At first, you might get a headache working to memorize a string of facts or to understand the process of mitosis or a new management strategy. But as you commit that information to memory, repeat it, practice rephrasing it and explaining it, it seems to become part of you so that you can talk about it familiarly. When it’s time to take a test on the subject, you have no trouble writing down the facts or composing an essay about the process.

Remember how distractible you were in the beginning, starting to try to learn that new information in a quiet room, plagued by thoughts of getting up to get a snack, do a chore, or follow the trail of any small distraction. Then remember how you could talk about it to others, even in a noisy environment with other things on your mind. Events which once distracted you didn’t get in the way once you really knew the information.

Learning in a Quality Environment

But we’re assuming you were allowed to learn the new information at the pace you needed, with your cognitive resources available and not stretched thin with lots of other activities. We’re assuming you were learning in a relaxed state without people pressuring you to hurry, to learn it faster, to just get the job done. You motivated yourself, knowing what you needed to achieve the goal and making sure you had it.

Dogs Need Us to Teach

Dogs depend on us to do all of this for them. They don’t seem to have any personal desire to learn some of the silly behaviors we ask them to do. We know the behaviors we’re teaching will make our dogs’ lives better, making dogs easier for us to live with, allowing them freedom to explore the world with us, and giving them more opportunities to have great experiences. We also know that we can teach them in a way that lets them volunteer for the opportunity to learn, once we get started.

Dogs probably think the big picture is fine the way it is, though. As a result, just as we have to motivate ourselves to learn, we are in charge of motivating our dogs. As their trainers, we start with thin slices of behavior that they can immediately succeed with. We select the behaviors to reinforce so we see them more often. We have the power to teach our dogs in appropriate environments and following the steps they need to achieve the goals we want for them. It’s our choice which cues our dogs respond to; we have to know just what the cues are and which other cues might conflict with them.

Sorting Out the Cues

Returning to our opening story, the student whose dog wanted to lie down on the mat whenever they came within 2 feet of it had the solution right in front of her: place the mat 3 or even 4 feet away and practice loose-leash walking in that scenario. When they became successful in those conditions, she could move the mat a little closer to practice further.

The mat was a distraction as well as a behavior she wanted the dog to maintain, so both leash skills and mat behavior needed practice separately. But both can easily become stronger behaviors as the dog learns to perform them in the presence of other opportunities. As handlers, we have to be able to understand what dogs are telling us, which in this case was, “Mom, the mat is a strong cue – like a magnet! I must go and lie down on the mat when it’s that close, and I can’t understand the leash cues when that mat is calling me!” We need to minimize the “call of the mat”, practice leash skills, and then start to systematically intensify the presence of the mat by moving it just a little closer to practice further.

“Training is Simple, Not Easy” – Dr. Bob Bailey

I’m sure you’ve seen dogs doing things like heeling around bowls of food, coming when called from playing with another dog or chasing a squirrel, or doing other behaviors that seem contrary to what a dog would normally like to do. Training is a process. Holding onto the vision of the behavior we want, we teach it in achievable increments, build it with positive reinforcement, then begin to move it into slightly more challenging environments. That’s all there is to it, really, but we have to be able to observe and understand a dog’s emotional state, cognitive load, and what he needs to be able to learn a new behavior. It’s our job to provide the training conditions our dogs need to succeed.