Balanced training for dogs: is just a little punishment helpful?

“Balanced training” seems to be a popular approach to dog training. Those who don’t understand behavior science think it’s a good approach, but it has zero support from science. A little scrutiny of balanced training for dogs reveals severe conflict between it and best training practices. In this article, I will share a little behavior science and a couple of stories. I hope to help you see the power of positive reinforcement when it’s used well.

Is it OK to say, “No!” to our dogs, or use one of the many available substitutes like, “Sssstt!” or “Aaahh!” to make them stop what they’re doing? For me, the answer is, “No, thank you.” I stopped using the word, “no” during training many years ago when I learned the benefits of positive reinforcement training over punishment training. I continue to learn new reasons for it to not be included in my training program.

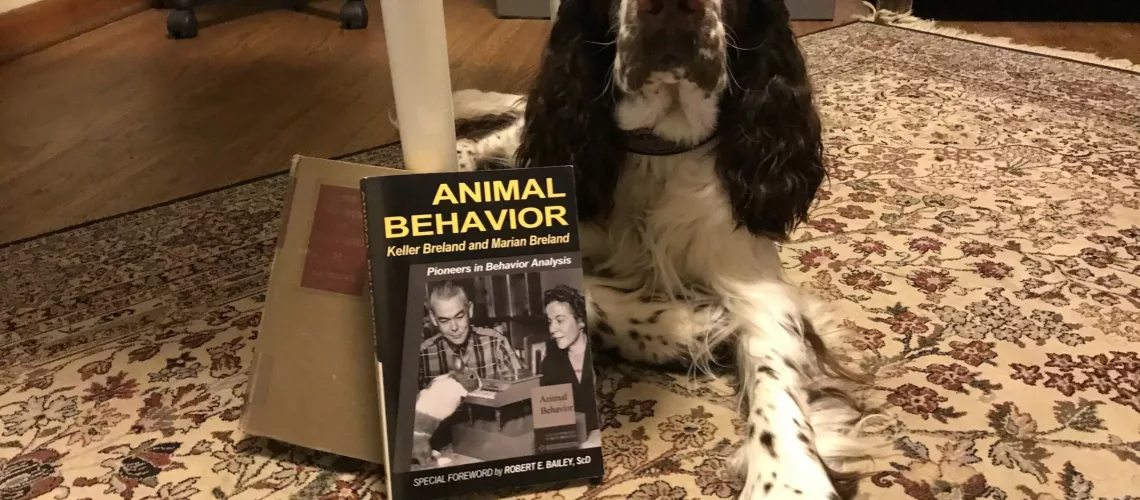

Jet and his owner

A little dog named “Jet” visited recently. He is a mixed breed about a year old, small and Schnauzer-like. He’s a bit fearful in demeanor, but his owner has trained him to do lots of behaviors. Trained behaviors, like “sit”, “down” and a couple of tricks give Jet confidence. They will serve him well in continuing to develop a more outgoing personality as he matures. Jet has also learned a couple of default behaviors that he chooses when he’s afraid or stressed.

Jet’s default behaviors

The first of Jet’s default behaviors is sitting and looking at his owner’s face. Jet sits at his owner’s right side and turns his head upward to latch gaze with his owner. He can hold this pose for a long time. His owner has built this behavior with lots of reinforcement; therefore, it holds plenty of value for Jet.

Jet’s second default behavior is lying under a chair. He relaxes to a degree, facing outward with a full view of the room. The owner explained that Jet has a favorite blanket. She didn’t purposefully train Jet to lie on that blanket, but he learned it well. Lying on the blanket is so reinforcing for Jet that his owner used it to train him to go under a chair. Lying under a chair now also holds a lot of value for Jet.

Training a “go to mat” behavior is helpful

Training a dog to go to a “mat” and then placing the mat in unusual places is a tried-and-true technique. Making it a little harder to get to the mat while building the value of the mat can help train a dog to go under tables, inside crates, or in this case, under chairs.

Jet used to be afraid to go under things like furniture. By placing his beloved blanket under tables and chairs, Jet learned to go under furniture. He even learned to go under things on cue, without the blanket. He will go under a chair when his owner says, “Get in your house.” He’ll go on his own when he feels stressed or needs a break. Jet’s owner is a budding trainer with very good observation skills and timing. I complimented her on these behaviors. Fearful dogs do well when they have a couple of default behaviors to rely on, and Jet’s owner had used this “go to mat” behavior with the blanket to Jet’s advantage.

Jet’s owner had brought the blanket along to my place. It sat inside a plastic grocery bag on a chair in my training room while we talked.

Balanced training for Jet

Jet’s owner was using balanced training, though she didn’t realize it had a name. She just thought it was a good idea to reinforce behaviors she liked and punish behaviors she didn’t like. During our visit, Jet’s owner used “No” and “Sssstt” several times. For instance, she said “No,” forcefully with with good timing, when Jet put his front paws up on her leg. Jet responded by immediately putting all four feet on the floor. It appeared this was what she wanted him to do. Later in our visit, Jet put his front paws up on the chair that held the plastic bag with his blanket in it. His owner said “Sssstt” and Jet immediately hopped off, placing all four feet on the floor. At that point, I told her how great I thought her training with Jet looked and suggested she stop scolding and reinforce more often.

The meaning of “Punishment”

Defined in behavior science, punishment or a punisher is a stimulus presented after a behavior that reduces or stops behavior. Were these words punishers? Yes, because they effectively stopped the behaviors Jet was doing when she used them. They were effective in the moment, but Jet later put his front paws up on other things. It’s likely these scolding words were not all that effective in the long run. But that’s not the only reason to reconsider this approach; they had an effect and though it seemed small, it was important.

First reason to avoid punishment

My reasoning for eliminating these “behavior-stoppers” was that she might want Jet to put his front paws up on something at a later time. Why try to remove this behavior from his repertoire? We had just been talking about tricks and beginning agility games for Jet. In both these training programs, the feet-up-on-a-chair behavior might be something she’d want to reinforce rather than punish.

As a related example, I explained why I teach my clients to trade their puppies or new dogs treats for things they have in their mouths, even if the items are valuable shoes or remote controls. It’s because trading develops the dogs’ retrieving skills, diminishing the risk of the dog running away with the shoe or remote and chewing it to shreds. If it’s rewarding to give the item to Mom, why not just take it right to her? Plus, why punish retrieving, when you might want to play ball with your dog at some point? Jet’s owner thanked me and said she had never thought about it that way before.

Good reasons to reinforce something else rather than punish

I suggested paying closer attention to Jet and reinforcing behaviors she liked. Sitting, lying down, playing with a toy, or many other behaviors could replace putting his feet up on people or chairs. As a last resort, she could re-direct him to a desirable behavior if she saw him start to raise his front paws. This would allow her to control the “paws up” behavior if she later wanted him to learn to touch high targets with his paw. She may want to use this behavior for touching contacts on agility obstacles. She thought that was a good idea. This was all in keeping with my habit of simply not saying “No” or punishing behaviors you might want later. But wait, there’s more. . .

What behavior was being punished?

Something about the visual scenario of my student scolding Jet while he was up on the chair caused it to continue rewinding and playing over and over again in my mind. I thought about it repeatedly through that night, and a very vivid imaginary snapshot kept popping into my head. There’s Jet, standing on his rear legs, front paws up on the chair with his head thrust forward. He was putting his nose on the bag containing his favorite blanket, the one used to teach the behavior of going under the chair! Remember, it was in a bag on the chair.

Jet had previously been afraid to go under a chair. He gained confidence and was able to do it when the precious blanket was employed as both a lure and reinforcement. What a powerful stimulus that blanket was! That’s something one should value as a training tool, being careful not to inadvertently diminish its value. Now I was seeing the use of her scolding, a punisher, in a whole new way. Oh, to have had a camera and the presence of mind to have taken an actual photo of that moment.

Punishment was destroying behavior that Jet’s owner liked

It’s likely Jet was punished for targeting his blanket. Remember, the owner thought she was scolding him for putting his paws up on the chair. While he was doing that, he was also reaching his head forward to touch the blanket in its bag with his nose. The scolding, if it worked, was diminishing all the behaviors Jet was doing when it happened.

The Matching Law

Why does such a small decision matter? Because every single thing a dog has ever learned is still with him. There’s lots of research that shows this, including Richard Herrnstein’s work on The Matching Law, published in 1961. It’s challenging enough to get another species to do what you want, without making it worse by being inconsistent and causing your dog to learn things that make your training work harder. Dogs take in everything they learn, and what they learn never goes away. But as a trainer, you have some control.

It teaches us that any behavior that has ever been reinforced is part of an animal’s repertoire.

This benefits us if our training is well-planned and executed.

It is detrimental if we’re not paying attention to what we’re teaching!

The Matching Law is not the only concern. As I described earlier, Jet targets that blanket to such a degree that his owner used it to train him to go under a chair. Targeting the blanket had been such a reinforcing behavior that it could be used to teach another behavior. Suddenly, we’re dealing with a potential Poisoned Cue. The famous video by Dr. Jesus Rosales-Ruiz and his graduate students showing their research with the “Ven-Punir” dog jumped to the forefront of my mind.

The Poisoned Cue

The Poisoned Cue study by Dr. Jesus Rosales-Ruiz and his graduate students details an experiment showing that a behavior trained using punishment cannot be used to reinforce a new behavior being trained.

showing that balanced training for dogs is not best practice.

The Premack Principle, commonly applied in dog training, explains that a behavior more likely to occur can be used to reinforce a behavior less likely to occur. A more colloquial description might be that the opportunity to perform an easy, “fun” behavior can reinforce the performance of a more-demanding behavior. For instance, the cue to retrieve something might reinforce a “stay” for a Golden Retriever if the Golden likes to retrieve.

teaching us that a series of behaviors can be developed

based on each behavior reinforcing the previous one.

The difference between reinforcement and punishment

In the video, the researchers used punishment to train a recall to a reliable level on the cue “Punir”*. (Nothing horrible – just a light collar jerk that many people use every day. The video clearly shows the dog in training flinching and pulling away from this annoying intrusion. Students of The Mannerly Dog don’t use this technique.) They then tried to use that recall to reinforce a new behavior being trained. The dog touched a target with his nose and then the trainer called him with the recall cue, “Punir”, giving him a treat when he came. Over several repetitions, the target behavior decreased, even though the dog got a treat for coming. Soon, the dog was reluctant to approach the target. This means the cue to come, “Punir”, was not reinforcing*. The punishment that came with the “Punir” cue was still with the dog; the neural pathways developed through that training process were still working. that stood in the way of the researchers’ ability to develop a chain of behaviors.

*Reinforcement is defined as something put into the training process after a behavior that causes the behavior to increase in frequency or strength. It’s the opposite of punishment as defined above, something put into the training process after a behavior that cause the behavior to decrease in frequency or strength.

Examples and effects

These may be new terms and definitions, so examples may help. If you give a dog a treat after a behavior, he may repeat that behavior more often – if so, you’ve reinforced the behavior. If you jerk your dog’s collar after he does a behavior, he may repeat that behavior less often. However, that punisher likely comes with emotional effects through association – fear of you or the environment, both of which were part of that punishment process. It’s just a fact. The concept of the “Poison Cue” rests on the fact that when an animal is not sure what the environment will offer, his behavior becomes less predictable because the environment is no longer predictable for him. Sometimes good stuff happens, sometimes bad, in his perception. This is the problem with balanced training for dogs.

The behavior backfired

When the researcher called the dog after he touched an object with its nose, the new targeting behavior, the one the researcher wanted to develop, subsequently decreased instead of increasing. The dog approached the target object quickly the first time. But after the trainer called him, his approach to the target next time was slow, his body language cautious as he tentatively approached again. Even though the dog received a treat when he came back to the trainer on the “Punir” cue, the target behavior continued to decrease. The researchers hoped they would reinforce the target behavior with the recall, using the Premack Principle. But the recall was punishing the new target behavior.

Premack works when positive reinforcement is used

The video shows the opposite, too. The researchers used positive reinforcement – treats after the correct behavior – to train a recall using a different cue, “Ven”**. The target behavior increased in frequency when they reinforced it with the cue “Ven”, which just happened to also mean “Come”. If an animal learns that a particular cue indicates a positive consequence, we can use that cue as a reinforcer, and the Premack Principle works in training. In this case, the dog touched a target, received the cue to come, “Ven”, which had always meant a treat was coming, and the target behavior increased. In the previous situation, the dog touched the target and received the cue to come, “Punir”, which had sometimes meant a treat was coming and sometimes meant a collar jerk was coming. This conflicting information from the dog’s environment caused the dog to produce conflicting, inconsistent behavior.

This experiment shows another interesting thing about training: both “Ven” and “Punir” were cues to come to the trainer. However, these were two different behaviors. Different cues and different reinforcement histories made them different. The lesson is that you can’t just look at the behavior; you must analyze the cue and the reinforcement or punishment that follows to determine what is really driving the behavior. That information provides the function of the behavior and it takes good observation skills to analyze what’s going on.

Contingency: when a cue predicts a reinforcer

When a cue coupled with a behavior has a history of leading to a reinforcer, you can use it to teach other behaviors. In our example of Jet and his blanket, the blanket itself was the cue. The reinforcement history showed that touching the blanket when it’s available (the behavior) had resulted in good things happening for Jet – that’s the reinforcement. With many dogs, this starts with a treat after the dog gets on a mat, which builds the value of the mat in the dog’s perception. In Jet’s case, it started with him feeling safe and secure on his blanket. Therefore, the blanket is a cue that means Jet gets to do something that he finds valuable. Lying on the blanket feels good. That’s reinforcing, and contingent on the presence of the blanket. The presence of the blanket is a clear, valuable cue.

What a great option for teaching Jet other behaviors! He could retrieve something, and the owner could make the blanket appear for him to lie on. (I would give a treat, too, for good measure.) Jet’s owner could teach him duration for a sit-stay by walking around him while he sat and then tossing the blanket down and releasing Jet to get on it. The opportunity to lie on the blanket would likely reinforce the behavior that preceded it because lying on the blanket already had a lot of value for Jet.

Using the Premack Principle in training

This is the Premack Principle: do a new behavior, or one that requires more work, then do a behavior that has a strong reinforcement history – a lot of value for the dog – then get a treat to top it off. This process mimics what performance dogs do in obedience and agility competitions. Each behavior leads to another behavior that training has built value for, and they all lead to the dog getting treats and playtime afterward. It’s a series of behaviors that produces happy anticipation at each level as the dog approaches closer and closer to the final reinforcer – treats, play, affection. (The Premack Principle is often explained as “Grandma’s Rule”: eat your spinach and then you can eat dessert!)

Non-contingency: when a cue can result in a reinforcer or a punisher

When a cue is poisoned, its history is that it sometimes leads to a reinforcer and sometimes to a punisher. The animal is confused, not knowing which will happen or what he can do to ensure a safe and desirable outcome for himself. Consider Jet and his blanket once again. If Jet touching his blanket had sometimes resulted in punishment and sometimes in reinforcement, the blanket’s history would be mixed and in the dog’s perception, unpredictable. The blanket would be a poisoned cue, never to be forgotten (refer to The Matching Law) and now lost as a training tool.

Revisiting the example of reinforcing retrieving behavior by presenting the blanket for Jet to lie down on, the blanket would result in mental conflict if it were poisoned as a cue. It may actually damage the new behavior of retrieving if the owner tries to use it as a reinforcer because it would not act as a reinforcer. Refer to The Poisoned Cue.

What about training with reinforcers and polishing with punishers?

In this era of blooming positive-reinforcement-based dog training, many trainers have taken the habit of using positive reinforcement to teach behaviors and then proofing or polishing them using punishment. A common belief is that a dog’s training must include punishment to eliminate any lingering possibility of an incorrect response to a cue. It’s common in the training of performance dogs for shows and competitions, in search and rescue and police work.

After training the dog’s behavior to fluency with reinforcement, the trainer may put the dog in a situation that encourages an incorrect response and physically punished when he does. The belief is that this is the final touch required to create reliability. Scientific research does not support this belief. Experimentation with poisoned cues shows that this final proofing can cause the trained behavior to deteriorate, though the problem may not show up until later. It would be more productive to systematically train the dog in this new situation rather than set him up to fail.

Balanced training: using both reinforcement and punishment to train

The Poisoned Cue is the problem behind so-called balanced training for dogs. People who say they practice balanced training reinforce some behaviors and punish others. Not understanding behavior science, this may seem like a good idea. However, the emotional responses to punishment can really slow training down. Dr. Julie Vargas, daughter of Dr. B. F. Skinner, talks about this in an upcoming documentary.

Could this be what causes dogs trained to a very high level to “suddenly” fall apart in an obedience competitions? Consider the dog competing in Utility Dog classes in AKC Obedience. The exercise requires the handler to cue the dog to go out to a pile of scent articles. The dog is to choose the one with the newest and warmest scent of his handler on it, pick it up and bring it back to his handler, sit in front of the handler while holding the object and release the article when the handler cues him to do so.

A real-life example from the dog obedience ring

The following scenario occurred in an obedience ring not too long ago: the handler gave the cue, the dog went quickly out to the pile and chose the correct article, carried it halfway back to the handler only to return to the pile, place the article back in it, search all the articles again and choose the same one. He began carrying it back to the handler and approached more and more slowly as he came closer, finally sitting in front to release the article to her. For this dog, did returning to his handler with an article cause conflict?

What is the history of this behavior for this dog? It seems that going to the pile, searching for the scented article, and picking it up are all reinforcing behaviors for the dog, since he did those quickly and even repeated them during the exercise. But returning to his handler with the article in his mouth was slow. The dog looked worried and tentative in his actions, indicating he may be conflicted about this behavior. After their ringtime, the handler said her dog’s hesitance to return to her was new, having developed over the course of this particular weekend of shows. What happened? What did the trainer change? Is it possible that in attempting to polish up the scent article exercise, this handler used punishment when the dog brought the wrong article? Perhaps the dog had needed more positive reinforcement training to choose the scented article. Perhaps the trainer had instead punished the dog for bringing back the wrong one. This is speculation since I don’t know the history of this performance team’s work.

Science-based training vs. balanced training for dogs

Exploring incidents like this help me to become better at analyzing behavior so that my own training continues to improve. In the obedience ring, each exercise can reinforce the previous one, creating a chain of behaviors ending with a primary reinforcer. After a reinforcing experience like this, a dog is ready to perform again the next time. I consider this a valuable scenario and like to preserve it by not taking the risk of punishing behaviors.

Many other situations deserve further behavior analysis with consideration of the poisoned cue. Examples include dogs who take off in the agility ring, running crazy, jumping random jumps and not returning to their handlers when called. Similar things happen in the obedience ring, too – loose dogs doing everything but return to their handlers. (Ask me about some of my early experiences with my own dogs in the obedience ring, before I learned how to train dogs really well!)

Balanced training for dogs may seem like a logical approach, but it’s loaded with damaging effects.

Conclusion: balanced training for dogs causes problems

I’ve always known that punishing a behavior may come with more baggage than we may realize at the time. I had thought of it in the context of, “Why punish this when we may want the dog to do it later?” It took Dr. Rosales-Ruiz’s presentation and video to start the wheels in my mind turning on this topic. By punishing one behavior, we may be damaging a whole chain of behaviors. Worse, we could destroy a wide variety of behaviors if one was implemented in training a lot of different things. It seems like reinforcing behaviors you like and punishing those you don’t like would be logical, but there are all kinds of problems. The problems are subtle at first but grow into monsters.

Skinner and the Brelands discussed unpredictable environments

Keller and Marian Breland discuss the concept of an unpredictable environment in Animal Behavior, published in 1966 (re-released in 2018). Dr. B. F. Skinner knew about it in the 1930s when he did his research, though none of these behavior pioneers used the term “Poisoned Cue”. The idea was simply that behavior is lawful. It follows laws just as gravity does. The predictability of the environment for the animal doing the behavior is crucial.

The potential damage is small but mighty

When I saw the poisoned cue effect happening on video, right before my eyes, it brought everything together for me. If a dog has a favorite toy, blanket, or behavior, it’s likely we’ll use that to reinforce many different behaviors during his life. In Jet’s case, the blanket is powerful, associated with lots of good things and at least one other strong behavior – going under a chair on cue. When Jet is worried, lying on that blanket makes him feel better.

Poisoning the blanket as a cue, as a reinforcer, will create conflict. Was Jet feeling stressed when he placed his front paws on the chair and his nose on the bag containing the blanket? Was he reaching for the blanket? “Asking” for it because he needed security? Will he now have to come up with another default behavior to use when he’s feeling insecure? Will that new default behavior be something we deem appropriate? So many questions, and so few answers. When we’re dealing with emotional responses like fear and insecurity, we’re opening up a whole new realm of possible damage to be done by punishing something we don’t realize we’re punishing.

“Pavlov is always on your shoulder.” – Dr. Robert E. Bailey

*”Ven” means “come” in Spanish.

**”Punir” means “to punish” in Spanish.